Signs

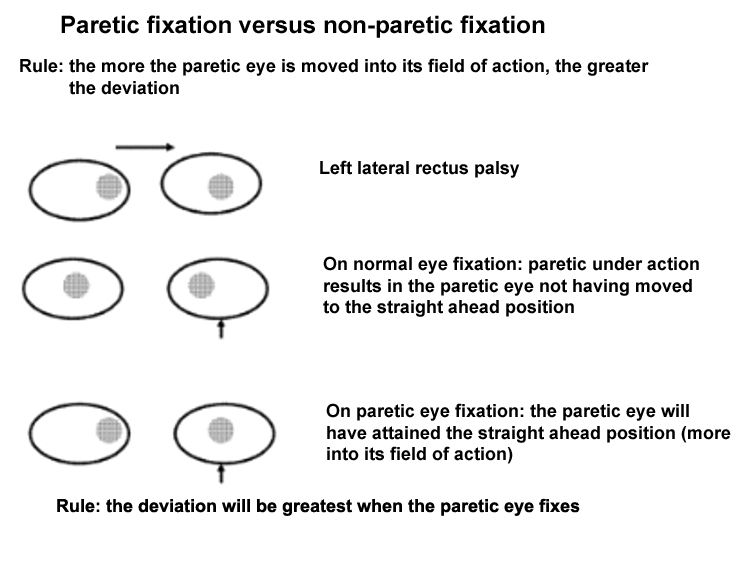

Most cases of sixth nerve palsy have an obvious esotropia making the diagnosis straightforward: that is, the affected eye has a convergent squint, but this may not be obvious in mild or partially recovered sixth nerve palsy1.

Complete paralysis of the abducens nerves is characterized by a large esodeviation in primary gaze, and clinically obvious limitation of abduction.

Incomplete or partial abducens paralysis is characterized by a smaller esodeviation in primary gaze with variable limitation of abduction, and lessening of the esotropia in other directions of gaze. Mild abduction weakness can be difficult to detect, blurring the distinction between abducens palsy and divergence insufficiency.

In mild cases, the best way to demonstrate the presence of the esotropia is by a cover/uncover test with distant fixation: with the cover/uncover test, the eye shows esotropia which is worse for distance than near (as is also the case for diplopia: worse for distance than near).

There is an A pattern esotropia on upgaze (since the lateral rectus acts best as an abductor on elevation).

There may be abnormal head posture with face turn to the affected side1, and slowing of abducting saccades2.

The term divergence insufficiency (DI) refers to a comitant esotropia that is greater at distance than at near with normal ductions. Affected individuals, predominantly adults, are neurologically normal and present with the insidious onset of horizontal diplopia at distance. Given the age predilection and normal neuroimaging, DI has been attributed to the progressive loss of fusional divergence amplitudes3.

Anatomical correlations

A selective lesion of the CN 6 nucleus causes a horizontal gaze palsy and not an isolated abduction paresis in one eye; therefore, patients with this lesion may not experience diplopia. This occurs because the CN VI nucleus contains 2 populations of motoneurons: (1) those that innervate the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle and (2) those that travel via the medial longitudinal fasciculus to innervate the contralateral medial rectus subnucleus of the CN III nuclear complex. Often, ipsilateral upper and lower facial weakness is also present with a nuclear CN VI palsy due to the adjacent facial nerve fascicle (eg, facial colliculus syndrome).

Intra-axial lesions of the CN 6 nucleus may also injure CN 7, whose fibers curve around the CN 6 nucleus at the facial genu.

- Intra-axial lesions that involve the CN 6 fascicle may also damage the CN VII fascicles, the tractus solitarius, and the descending tract of CN 5, resulting in an ipsilateral abduction palsy, facial weakness, loss of taste over the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and facial hypoesthesia (Foville syndrome).

- Lesions of the ventral pons can damage CN 6 and CN 7 along with the corticospinal tract, producing contralateral hemiplegia, ipsilateral facial weakness, and abduction deɹcit (Millard-Gubler syndrome).

The abducens nucleus is located dorso-ventrally at the pontomedullary junction. Motor nerve fibers course ventrally through the pons after exiting the abducens nucleus and form the abducens nerve fasciculus.The fibers then exit the brainstem near the midline to form the abducens nerve, emerging from the horizontal sulcus in between the pons and medulla, just lateral to the bundles of the corticospinal tract, and which runs rostrally along the surface of the clivus within the subarachnoid space anterior to the basilar pons, passes under the petroclinoidl ligament through the Dorello canal, and enters the cavernous sinus. The nerve then runs through the cavernous sinus in close association with the internal carotid artery and passes into the orbit via the superior orbital fissure, within the annulus of Zinn, to innervate the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle.

The subarachnoid segment of the ocular motor CNs extends from the brainstem to the cavernous sinus, where the nerves exit the dura.

Causes

- Isolated CN VI palsies in adults older than 50 years are usually ischemic.Most ischemic CN palsies occur in the section from the brainstem to the cavernous sinus. Ischemic cranial mononeuropathies typically occur in isolation, with maximal deɹcit at presentation, but occasionally the loss of function progresses over 7–10 days. Pain may or may not be present; if present, it may be quite severe in some patients. Ocular misalignment due to ischemic ocular motor CN palsy almost always improves over time, and the diplopia usually resolves within 6 months. Patients require medical evaluation for ischemic risk factors. Progression of ocular misalignment beyond 2 weeks or failure to improve within 3 months is inconsistent with an ischemic cause of a cranial neuropathy and should prompt a thorough evaluation for another etiology.

- The nerve is susceptible to injury from shearing forces of head trauma or elevated intracranial pressure. In such cases, injury occurs where CN 6 enters the cavernous sinus through the Dorello canal.

- May be the only presenting ocular sign of a posteriorly draining carotid-cavernous fistula

- After exiting the prepontine space, CN 6 is vulnerable to meningeal or skull-based processes, such as meningioma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, chordoma, or chondrosarcoma if the patient has a history of cancer and an ocular motor cranial neuropathy is present, neuroimaging should be performed to rule out a compressive or inɹltrative lesion.

- Lesions of the cerebellopontine angle (especially acoustic neuroma or meningioma) may involve CN 6 and other contiguous CNs, causing decreased facial and corneal sensation (CN 5), facial paralysis (CN 7), and decreased hearing with vestibular signs (CN 8).

- Chronic inflammation of the petrous bone may cause an ipsilateral abducens palsy and facial pain (Gradenigo syndrome), especially in children with recurrent middle ear infections.

- Myasthenia gravis

- Thyroid eye disease

- Leukemia and brainstem glioma are important considerations in children.

- Multiple sclerosis

- Medial orbital wall fracture with entrapment

- An abduction paresis that is present early in life usually manifests as Duane syndrome

- Spasm of the near reflex

- Approximately 10%–15% of patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA) may present with diplopia from a skew deviation, ischemic cranial neuropathy, or extraocular muscle ischemia.

Neuroimaging and isolated CN 6 palsy

Whether or not neuroimaging is required at the time of initial diagnosis is controversial. Some experts recommend neuroimaging at the time of initial presentation. As with other isolated ocular motor cranial nerve palsies, medical evaluation is appropriate. However, a cranial MRI is mandatory if obvious improvement has not occurred after 3 months. Other diagnostic studies that may be required include lumbar puncture, chest imaging, and hematologic studies to identify an underlying systemic process such as syphilis, sarcoidosis, collagen vascular disease, or GCA. Impaired abduction in patients younger than 50 years requires careful scrutiny because few such cases are caused by ischemic cranial neuropathy. Younger patients should undergo appropriate neuroimaging.

From: Chua CN. Success in ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.mrcophth.com/ocularmotility/sixthnerve.html

Image from: Barton J. Abducens (VI ) nerve palsy. Retrieved from: http://www.neuroophthalmology.ca/textbook/disorders-of-eye-movements/iv-neuropathies-and-nuclear-palsies/v-abducens-vi-nerve-palsy

Canadian Neuro-Ophthalmology Group: Abducens (VI) nerve palsy