The cerebellum plays a pivotal role in the control of eye movements. Its core function is to optimize ocular motor performance so that images of objects of interest are promptly brought to the fovea – where visual acuity is best – and kept quietly there, so the brain has time to analyze and interpret the visual scene1.

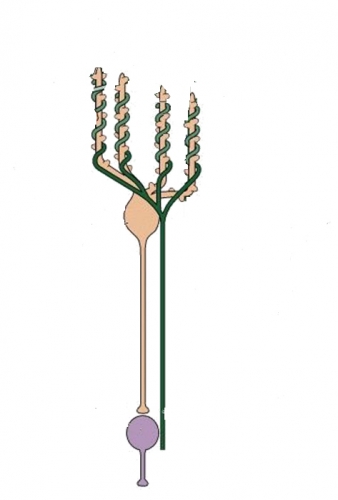

The cerebellum has both immediate, on-line functions to make each individual movement accurate, and long-term, adaptive functions to keep ocular motor responses correctly calibrated to the stimuli that drive them. The cerebellar cortex can be thought of as a parallel pathway that oversees and influences (via the projections of its Purkinje cells) the direct flow of information to and from the brain stem through the deep cerebellar nuclei2:

- Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex primarily project to and inhibit cells within the underlying deep cerebellar nuclei.

- The fastigial nuclei decussate within the cerebellum and terminate in the contralateral vestibular or premotor brainstem nuclei.

- Purkinje cells in the vestibulocerebellum (flocculus,paraflocculus,nodulus, and uvula) project primarily to the ipsilateral brain stem nuclei and the vestibular nuclei (some of which can be thought of as “displaced” deep cerebellar nuclei)2.

Cerebellar Lesion |

|

|

|

Abnormal pursuit, with impaired visual suppression of the VOR Downbeat and rebound nystagmus. Pathological ocular alignment in viewing at a distance (esophoria, esotropia) |

|

|

Periodic alternating nystagmus. |

|

Lesions of dorsal vermis: hypometric saccades Lesion of Fastigial N: hypermetric saccades |

Other types of eye movement abnormalities also occur with cerebellar dysfunction but are poorly localized1:

- Various forms of saccadic intrusions, such as square-wave jerks, macrosaccadic oscillations, and ocular flutter, may be associated with cerebellar pathologies and often degrade vision.

- Gaze holding deficits3. In one study, 80% of patients had gaze evoked nystagmus3.

- Central fixation nystagmus3.

- Central positional nystagmus3; may be seen with lesions of the nodulus/uvula, but localization is poorly understood.

- Skew deviation that often changes direction with horizontal eye position (alternating skew deviation) is seen with the abducting eye usually being higher, producing a pattern of right hyperdeviation in right gaze and left hyperdeviation in left gaze. It is presumed that the origin of the skew might be an imbalance in otolith-ocular projections to the cerebellum.

- Head shaking-induced nystagmus (sometimes perverted, oppositely directed to the spontaneous nystagmus, or with a quick, large-amplitude reversal, or vertical when horizontal head-shaking3).

- Downbeating positional nystagmus

- Direction-changing, horizontal apogeotropic positional nystagmus (ie, beating to the sky with one ear down).