When the head is tracking a moving target, or when a fixation target is moving at the same velocity as the head (as in reading while moving in a vehicle) the VOR is normally suppressed or cancelled in order to maintain a stable image: the VOR is essential for maintaining stable vision on a target when the head is moving, but the brain requires a mechanism for suppressing the VOR during combined eye-head tracking (as in visually pursuing a target moving slowly from right to left off in the distance, where the head and eyes rotate together, rather than in opposition). VOR cancellation is managed by the vestibulocerebellum and, in particular, the flocculus and paraflocculus (the smooth pursuit system)1. These cerebellar neurons likely receive visual input from direction-specific, parieto-occipital motion-sensing neurons, and a related population of frontal eye field neurons1.

Since smooth pursuit cancels the VOR, visual cancellation of the VOR is an important test for the pursuit system.

Testing

Prior to testing the visual cancellation of the VOR, the examiner should ensure that the VOR is intact, typically by performing the head impulse test.

Note that in bilateral vestibulopathies, visual suppression of the VOR will appear to be normal, since the VOR is not working2.

The VOR cancellation test cannot be used to effectively assess VOR cancellation in the presence of primary-position nystagmus (for example, congenital nystagmus)1.

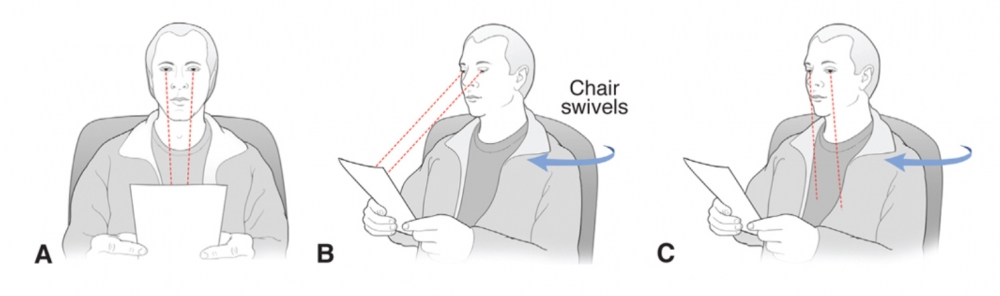

VOR cancellation can be assessed at the bedside by asking the patient to clasp their hands together in front of them, and to fix their vision on their outstretched thumbs while rotating the head and arms together in a swivel chair. The patient must maintain gaze in the primary position throughout the rotation.

The rotation is from side to side, about 30 degrees to either side1. The entire sweep from one side to the other should last 1.5 to 6 seconds, and passes of increasing velocity may be useful to determine the range in which the VOR cancelling system is functioning optimally.

The target moves at the same speed as the patient’s head, and therefore, normally, the eyes should not move at all in the orbit during this manoeuvre, since the angular velocity of the target is matched by the angular velocity of the subject's head. Certainly, the eyes should be stationary in the mid-position throughout the middle of each side-to-side pass, although the eyes may slip off the target and demonstrate several nystagmoid re-fixation jerks at the ”turns” (ie, during peak deceleration and acceleration) and this should not be over-interpreted1.

The test can be adapted for use in assessing cancellation of the vertical VOR by using the same fixation target (outstretched thumbs), and assisting the patient through several cycles of trunk flexion and extension.

With inadequate VOR cancellation:

-The eyes are taken off target by VOR slow phases in the opposite direction to that of the head movement, which leads to corrective saccades which re-establish fixation on the target3. The quick phases are in the direction of head rotation.

-The patient will develop repetitive refixations (nystagmoid jerking) during the middle of each rotational pass (fixed-velocity segment).

-When VOR cancellation is more severely affected, corrective saccades will occur at lower velocities and be more prounced2.

-Deficient VOR cancellation on rotation to the left corresponds to low pursuit gain to the left4.

A. The patient is seated in a swivel chair, fixating on the letters of a near card held at arm’s length.

B. If VOR suppression is normal (intact), the eyes maintain fixation on the target as the chair, the patient’s head and arms, and the card rotate together as a unit.

C. Conversely, if VOR suppression is impaired, the eyes are dragged oʃ target during rotation due to an inability to cancel the VOR. In this example, the chair is rotated to the patient’s right, and the VOR moves the eyes to the patient’s left, prompting a rightward saccade to regain the target; this result likely indicates right cerebellar system pathology

Causes

VOR cancellation may be impaired by lesions anywhere along the hemispheric pathway to the brainstem and vesibulocerebellum (including parietal and frontal lobes, and pons), but severe and relatively isolated findings are found with lesions of the flocculus and paraflocculus.

Since gaze-evoked nystagmus can result from vestibular disease via a non-cerebellar mechanism, and breakdown of smooth pursuit tracking is often a nonspecific, non-localizing manifestation of age-related brain changes, abnormalities of VOR cancellation are usually more specific markers of vestibulocerebellar dysfunction in patients with dizziness or vertigo. Poor VOR suppression is seen in patients with cerebellar disease, especially with lesions of the flocculus, a component of the vestibulo-cerebellum1.

A number of medications have also been associated with poor VOR suppression, including antiepileptic drugs, sedatives, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Increased VOR amplitude (gain) is commonly seen in patients with cerebellar lesions, for example, due to multiple sclerosis, and is characterised by slow phases that are too fast, necessitating back-up corrective saccades during head motion.

Indication

- In patients with vestibular symptoms, where it may be difficult to distinguish between the vestibulocerebellum and the peripheral vestibular system, the finding of abnormal VOR cancellation, especially with associated gaze-evoked nystagmus and impaired smooth pursuit, is suggestive of localization to the vestibulocerebellum, since VOR cancellation is a test of the smooth pursuit system.

- In patients with bilateral gaze-evoked nystagmus, there may be difficulty in establishing whether this represents physiological end-point nystagmus, or is due to failure of gaze-holding mechanisms due to cerebellar disease. In the event that impaired VOR cancellation is found, that would suggest cerebellar disease, rather than physiologic nystagmus.

- In patients with unilateral gaze-evoked nystagmus, this finding may be due to either unilateral cerebellar disease (eg, cerebellar stroke) or unilateral peripheral vestibular disease (eg, vestibular neuritis) (mild enough, or visually suppressed enough) to be present only in the lateral gaze position), (known as “first degree” peripheral vestibular nystagmus). In these cases, the presence of VOR cancellation failure suggests a central cause.

Note this is a constant rotation in one direction.

(vv)VORSuppression.mp4(tt)

Many thanks to the long suffering Dr Brey

(vv)VOR_Suppression_.mp4(tt)

Gold D. VOR (Suppression). Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL Web Sit. 2016. Available at: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6bw0r9q

(vv)abnormalVORsuppressionLflocculus.mp4(tt)

From: Clinical Examination of the Ocular Motor and Cerebellar Ocular Motor System. Strupp, M. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=meXAjVoQdCI

(vv)VORsupp.mp4(tt)

From: Halmagyi GM. Clinical Examination of the Vestibular System. J Vestib Res. Teaching Course, 29th Bárány Society Meeting, Lecture 2, June 5, 2016, Seoul, Korea.

From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehR7SOlBBow