Nystagmus can degrade visual acuity, produce oscillopsia, and exacerbate gait instability and spatial disorientation.

Classically, nystagmus begins with a slow drift of the eyes taking the line of sight away from the object of regard before it is brought back toward the object of regard with the fast phase.

Jerk nystagmus also may be physiologic, such as occurs during natural rotation of the head, and in this case the slow phase ensures rather than disrupts steady fixation1.

Pathological nystagmus reflects abnormalities in the mechanisms that hold images on the retina (the vestibulo, optokinetic and pursuit systems, and the neural integrator). A disturbance of any of these mechanisms may cause drifts of the eyes, the slow phases of nystagmus, during attempted steady fixation. Corrective quick phases or saccades then reset the eyes. Note that normally, when the head is still, the left and right vestibular nerves and the neurons in the vestibular nucleus to which they project have equal resting discharge rates (vestibular tone) 2. Movement of the head toward one side excites that labyrinth and inhibits the other. If the tone becomes relatively less on one side, such as due to an acute pathological lesion, spontaneous nystagmus develops, with slow phases directed toward, and quick phases directed away from the “lesioned” side.

The intensity of nystagmus often depends on the position of the eye in the orbit (Alexander’s law): with peripheral lesions the slow-phase velocity is higher when gaze is in the direction of the quick phase. With central lesions the opposite sometimes occurs.

A vestibular tone imbalance in the:

- Yaw plane shoud give rise to horizontal (right or left beating) spontaneous nystagmus

- Pitch plane shoud give rise to vertical (up or downbeating) nystagmus 3

- Roll plane shoud give rise to torsional nystagmus.

Characteristics of Nystagmus1, 4

1. Pendular versus jerk: Nystagmus is called “jerk” when the returning eye movements are saccades (with a slow phase, and a fast phase), and “pendular” when there are only slow phases.

2. Plane: horizontal, vertical, torsional, or combined form (eg, rotary, elliptical)

3. Conjugacy

-Conjugate: Both eyes move in the same direction with similar amplitude and velocity.

-Disconjugate: Both eyes move in the same direction with different amplitude and velocity(e.g., internuclear ophthalmoplegia).

-Disjunctive: The eyes move in opposite directions (eg, oculomasticatory myorhythmia seen in Whipple’s disease).

4. Amplitude

5. Velocity: slow-phase velocity is the most useful measurement for quantifying the intensity of the nystagmus.

6. Slow-phase waveform: this reflects changes in velocity over time, that is, decreasing, increasing, or constant velocity.

7. Frequency. Nystagmus associated with oculopalatal tremor is characteristically of low frequency.

Note:

In the supine position with the right ear “down” (ie, supine subject with neck rotated toward the right shoulder), nystagmus that beats towards the earth is often referred to as “geotropic” rather than “right-beating,” especially if its direction with respect to the head reverses after the head is reoriented to the left ear “down” supine position (ie, now “left-beating” but still “geotropic”).

In this nomenclature and using an earth-referenced frame, nystagmus which beats away from the earth is called apogeotropic. Such terminology is restricted to use with positional testing1.

Nystagmus with eyes in primary position

Firstly, note that nystagmus should be distinguished from saccadic intrusions and oscillations. In nystagmus, the eyes drift away from the fixation target due to a pathological slow eye movement, whereas the eyes become off-target due to unwanted saccades in saccadic intrusion and oscillations.

In the primary position of gaze (gaze straight ahead), the question is whether the nystagmus present is due to fixation nystagmus or spontaneous nystagmus5.

- Fixation nystagmus, which may increase when the patient tries to fix on a particular point, is typically caused by a central disorder (brainstem/cerebellar), and is commonly congenital.

- Spontaneous nystagmus: nystagmus present while looking in the straight-ahead (center) gaze position with the head stationary in the upright and neutral position. Typically modified (increased or decreased in intensity) in one or more positions of gaze1.

Nystagmus with Gaze

Pathologic nystagmus generally results from disruption of one or more mechanisms that normally hold gaze steady—disturbance of the vestibulo-ocular reflexes, failure or instability of the mechanism for gaze-holding (the neural integrator), or disorders of the visual pathways that impair the ability to suppress eye drifts during attempted fixation. Such disturbances may be acquired or may be due to congenital or early developmental abnormalities1.

Nystagmus may be triggered or modulated by various manoeuvres, such as eccentric gaze (gaze-evoked nystagmus, GEN), as well as other manoeuvres such as horizontal headshaking, and positional changes.

Position changes include:

-Positioning nystagmus, due to peripheral vestibular disease, is caused by the actual head movement. This is paroxysmal, and can be found in disorders such as benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV), Ménière’s disease, vestibular atelectasis, physiological “head extension vertigo” or “bending over vertigo".

-Positional nystagmus is caused by a specific head position (secondary to a central lesion).

Note that in most cases, the terms positioning and positional are used interchangeably and useage of a strict definition (as indicated above) is uncommon6.

The distinction between GEN and physiological/endpoint nystagmus is a common problem:

-Many healthy subjects have physiological end-point nystagmus during maximal eccentric gaze, and the nystagmus is generally of low amplitude, low frequency, poorly sustained (often just a few small beats of nystagmus are seen in each direction), binocular, and symmetric on right and left gaze1. It may occasionally be sustained, asymmetric, or slightly dissociated.

-Indications that the nystagmus may be pathological include its duration (if it lasts for longer than 20 seconds, since typically of 5-10 seconds duration), and asymmetry7. End-point nystagmus may have a slight torsional component in some normal people6. Pathologic gaze-evoked nystagmus is usually associated with other ocular motor findings such as impaired smooth-pursuit and rebound nystagmus8. Associated rebound nystagmus (change in direction of nystagmus when the eyes return to primary position from a previously held eccentric gaze) is indicative of pathological GEN.

(vv)BaranyPhysiologicendpointnystagmus.mp4(tt)

From: Committee for the International Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Barany Society.1.1.Physiologic Nystagmus. Retrieved from http://www.jvr-web.org/images/1.1.-Physiologic-endpoint-nystagmus.m4v

Central and Peripheral Nystagmus

The typical direction in which peripheral vestibular spontaneous nystagmus beats is horizontal-rotating towards the non-affected side.

Classically, purely horizontal or vertical spontaneous nystagmus is of central origin, although potentially any trajectory may be found.

The central origin of the nystagmus may be evident since the trajectory is incompatible with usual forms of peripheral vestibular dysfunction which affect a specific semicircular canal. Note that nystagmus of central origin may occasionally have a pattern which mimics peripheral vestibular lesions.

However, nystagmus of central origin may be distinguished from peripheral nystagmus by a number of specific features on examination, see: Section on Vestibular Disease: Separating Peripheral from Central Nystagmus

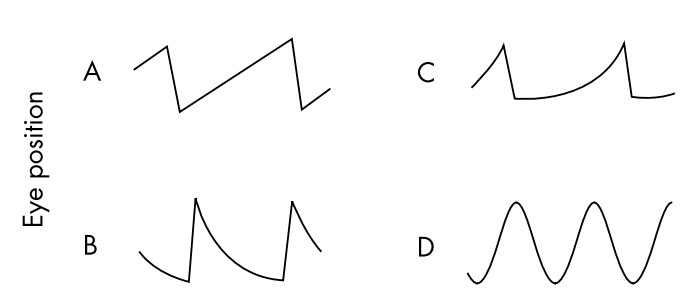

(A) Constant velocity drift of the eyes, with corrective quick phases, typical of peripheral or central vestibular disease.

(B) Drift of the eyes back from an eccentric orbital position toward the midline (gaze evoked nystagmus). The drift shows a negative exponential time course, with decreasing velocity. This waveform reflects an unsustained eye position signal caused by an impaired gaze holding mechanism.

(C) Drift of the eyes away from the central position with a positive exponential time course (increasing velocity). This waveform is encountered in the horizontal plane in congenital nystagmus.

(D) Pendular nystagmus, which is encountered as a type of congenital nystagmus and with acquired disease9.

Figure from: Serra A, Leigh RJ. Diagnostic value of nystagmus: spontaneous and induced ocular oscillations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(6):615-8.

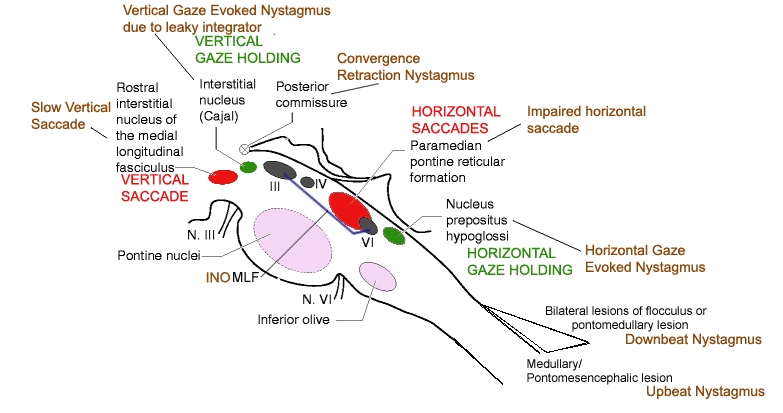

GEN typically indicates a structural lesion affecting the gaze holding systems:

- Consequently, horizontal GEN is due to a lesion of the neural integrator for horizontal gaze-holding function:nucleus prepositus hypoglossi, vestibular nuclei, and cerebellum (flocculus/paraflocculus(tonsil)).

- In the case of vertical gaze evoked nystagmus, GEN would be observed in midbrain lesions involving the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC): the neural integrator for vertical gaze-holding function. Such nystagmus is highly unlikely to be peripheral since pure vertical nystagmus can only be induced by simultaneous stimulation of the same vertical canal on both sides; similarly, pure torsional nystagmus can only be produced by stimulation of both the anterior and posterior canals on one side, and is therefore usually seen in central lesions4.

Redrawn from: Struppp M. Clinical Examination of the Ocular Motor and Cerebellar Ocular Motor System. J Vestib Res. Teaching Course, 29th Bárány Society Meeting, Lecture 2, June 5, 2016, Seoul, Korea.From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=meXAjVoQdCI

| Abnormal Eye Movement |

|

|---|---|

| Downbeat nystagmus | Cranio-cervical junction |

| Upbeat nystagmus | Posterior fossa (medulla commonest) |

| Periodic Alternating nystagmus | Cerebellar nodulus |

| See saw nystagmus | Parasellar region/diencephalon |

| Ocular flutter/opsoclonus | Pons (pause cells), cerebellum |

| Convergence retraction nystagmus | Pretectum (dorsal midbrain) |