Positional and positioning vertigo and nystagrnus syndromes can be attributed to either peripheral or central vestibular dysfunction.

The most common form is benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo, BPPV, which is caused by cupulolithiasis in the posterior semicircular canal. The diagnosis is suggested by a history of brief (less than one minute) episodes of vertigo that are provoked by rolling over in bed, lying down, sitting up from a supine position, bending over, or looking up. BPPV commonly is worse in the early morning (matutinal vertigo), and may be absent for weeks or months at a time before returning1.

In addition to attacks of positional vertigo, patients may have prolonged mild unsteadiness, even after successful treatment of BPPV. It is important to note that patients with an acute vestibular syndrome will report exacerbation with head movement, and this should be distinguised from BPPV being triggered by head movement2.

Other causes of positional vertigo include:

- Alcohol toxicity

- Meniere's disease

- Vestibular migraine

Vertigo which may be dependent on head or neck position includes:

Vertigo that is absent at rest and is brought on only by lying down, turning over in bed, bending down, or arching back is likely to represent BPPV. However, spontaneous nystagmus can enhance in the supine position, leading to an incorrect diagnosis of positional vertigo. For example, a subject with left vestibular neuritis could demonstrate dramatic enhancement of subtle right-beating nystagmus in either Hallpike position2.

Pathophysiology

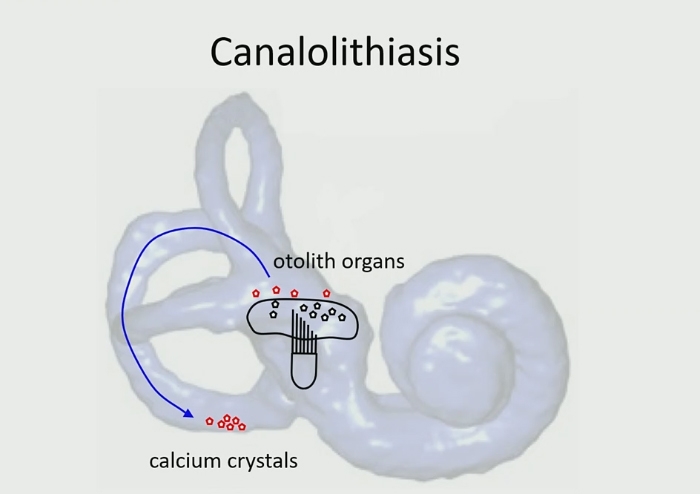

The cupula forms an impermeable barrier across the ampulla, and therefore, particles in a semicircular canal can only enter and exit through the end without an ampulla.

Posterior canal BPPV is due to particles which detach from the otoconial layer of the macula of the utricle by spontaneous degeneration or as a result of head trauma, and which then gravitate to and lie in the lowest point of the posterior semicircular canal. This canal lies immediately inferior to the utricle when the head is upright: the posterior semicircular canal thus serves as a receptacle for the detached sediment (Figure 1). Frequently, a clot may be formed overnight and give rise to symptoms in the morning.

Normally, the semicircular canals are excited only by head rotation; however, when particles which are more dense than endolymph are present in the lumen the canals become gravity sensitive, pathologically responding to changes in head position1.

In canalolithiasis, where the otoconia lie within the canal, after a change in head position in the plane of the affected canal, gravity causes the otoconia to move. The resulting inappropriate endolymph flow,, deflects the cupula and, by stimulating the posterior canal, informs the brain that the head is moving in the plane of that canal, resulting in attacks of positional vertigo and nystagmus. Deflection of the cupula continues until the movement of the otoconia stops.

In cupulolithiasis, BPPV can be attributed to otoconia that are attached to the cupula of a semicircular canal and render it sensitive to gravity. In this case, positioning manoeuvres will result in a nystagmus which commences immediately, and which tends to persist.

In most cases, BPPV is the result of canalolithiasis, with otoconia moving freely in the semicircular canals3.

Causes

1. Head injury

2. Vestibular neuritis

3. Following a long period of bedrest3

4. Following surgery, including dental work

Natural History

BPPV may develop in the affected ear within a few weeks after an attack of vestibular neuritis, which suggests a loosening of the otoconia due to labyrinthine inflammation4. The rate of spontaneous recovery is high, over 60% within a month, but BPPV persists in about 30% of patients5.

In BPPV, there are multiple stereotyped, head-position-provoked episodes that are brief, lasting seconds, and which occur multiple times per day for days or even weeks. The attacks eventually remit spontaneously in most patients, presumably because the otolithic debris dissolves or is dislodged through the course of normal activity.

Patients may have suffered their last symptoms some time prior to the visit, and in these cases, it is typical that the Dix-Hallpike test is negative.

There are very few diseases that mimic the classic history for BPPV, and the closest mimics (the central positional vertigo syndromes) tend not to remit spontaneously. Therefore a negative Dix-Hallpike test should not preclude the diagnosis of BPPV. A history of bouts separated in time (weeks, months, or years apart) is further evidence supporting the diagnosis6.