Attacks of Menière's disease are characterized by recurring postural vertigo persisting for a time ranging from minutes to hours and accompanied by hearing impairment, tinnitus, and a feeling of pressure in the affected ear.

Occasionally the vertigo is preceded by amplified ear noises, increased ear pressure, or reduced acuity of hearing1.

The disease usually involves one ear (unilateral Meniere’s disease), but it may affect both ears (bilateral Meniere’s disease) from the onset of the disease or several years later2.

An episode of acute vertigo in Meniere disease is characterized by typical peripheral nystagmus that is unidirectional, obeys Alexander’s law, and is enhanced in the dark. In contrast to other peripheral vestibular disorders, the nystagmus may initially beat toward the affected ear (irritative nystagmus), and then, within seconds to minutes, change direction to beat toward the unaffected ear (paretic nystagmus), and finally change direction once more (recovery nystagmus) to beat to the affected ear. This sequence of direction change in primary position spontaneous nystagmus has only been reported in endolymphatic hydrops3.

Attacks of sudden loss of vestibulo-spinal reflexes resulting in sudden falls or lateropulsion, and lasting seconds or, rarely, a few minutes, can occur (so called drop vestibular attacks, otolithic crises or Tumarkin’s otolithic crises4.

Pathogenesis

The etiology and pathophysiology of Menière's disease is likely to be due to an accumulation of endolymph in the cochlear duct

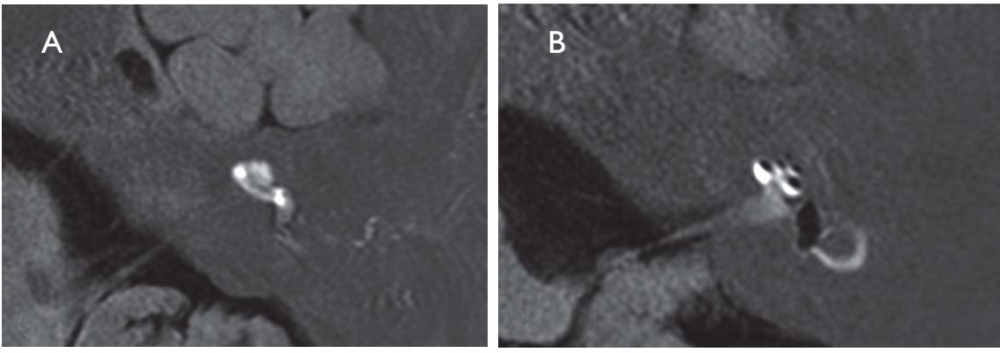

The pathognomonic histopathological finding is endolymphatic hydrops, which is evident on high resolution MRI of the petrosal bone after transtympanic injection of gadolinium (Figure 1). However, endolymphatic hydrops can be found in the saccule in 10% of normal individuals and in 40% of patients with greater than 45 dB SNHL without any vestibular symptoms2.

The attacks probably arise from the opening of pressure-sensitive cation channels and/or rupture of the endolymphatic membrane with increased potassium concentration in the perilymphatic space, which leads to excitation and then to depolarization of the axons.

Criteria for diagnosis of Menière’s disease4

A. Two or more spontaneous episodes of vertigo, each lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours.

B. Audiometrically documented low- to medium frequency sensorineural hearing loss in one ear, on at least one occasion before, during or after one of the episodes of vertigo.

C. Fluctuating aural symptoms (hearing, tinnitus or fullness) in the affected ear.

Cluster analysis reveals different groups of patients2. In patients with bilateral involvement:

- Menière’s disease type 1 (almost half of patients) was defined by sensorineural hearing loss starting in one ear and involving the second ear in the following months or years but without migraine and autoimmune comorbidities.

- Menière’s disease type 2 was characterized by simultaneous onset of hearing loss in both ears without migraine or autoimmunity.

- Menière’s disease type 3 was familial

- Menière’s disease type 4 was associated with migraine in all cases.

- Menière’s disease type 5 was associated with an autoimmune disease.

A. The labyrinth of a healthy control: The cochlea and semicircular canals are visualized.

B. The labyrinth of a patient with Menière's disease: the endolymphatic hydrops can be recognized by virtue of its lack of contrast medium uptake.

Redrawn from: Strupp M, Dieterich M, Brandt T. The treatment and natural course of peripheral and central vertigo. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(29-30):505-15.

In this patient with left Meniere’s disease, spontaneous, binocular, conjugate, jerk nystagmus beats in a single plane and direction (to the right) regardless of gaze position. With visual fixation removed, the nystagmus follows Alexander’s law: present in straight ahead gaze, increasing in intensity when looking toward the fast phase direction in rightward gaze, and almost disappearing, but still right-beating when looking toward the slow phase direction in leftward gaze. During visual fixation, the right-beating nystagmus is significantly suppressed, but still present in straight ahead gaze, again increasing in rightward gaze but disappearing with leftward gaze (thus considered “second degree” vestibular nystagmus during fixation).

(vv)BaranySVN.mp4(tt)

From: Committee for the International Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Barany Society.2.1.1. Spontaneous peripheral vestibular nystagmus. Retrieved from http://www.jvr-web.org/images/2.1.1.-Spontaneous-peripheral-vestibular-nystagmus.m4v