Transient attacks of vertigo of central origin are the commonest early symptom of basilar insufficiency because of the steep pressure gradient from the aorta to the terminal pontine arteries, which are long, tenuous, circumferential arteries and therefore are a vulnerable blood supply for the vestibular nuclei.

Transient ischemia of the labyrinths may also contribute. Vestibular vertigo and ataxia and drop attacks may potentially be precipitated by extension or rotation of the neck, for example when a partial obstruction of the arteries combines with a sudden fall of systemic blood pressure, eg, in a patient rising from a chair and looking up1.

The cardinal manifestations of Rotational Vertebral Artery Occlusion Syndrome (RVAOS) are2:

- Promptly reversible occlusion of the VA during head rotation

- Promptly reversible symptoms

Most patients with RVAOS exhibit a stenosis or anomaly of the vertebral artery (VA) on one side (eg, hypoplasia or termination in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery) associated with the dominant vertebral artery being compressed at the C1-2 level during contraversive head rotation, which causes compromise of the blood flow in the vertebrobasilar artery territory3. Hemodynamic compromise observed in RVAOS indicates that isolated vertigo and nystagmus may occur due to transient ischemia of the inferior cerebellum or lateral medulla4.

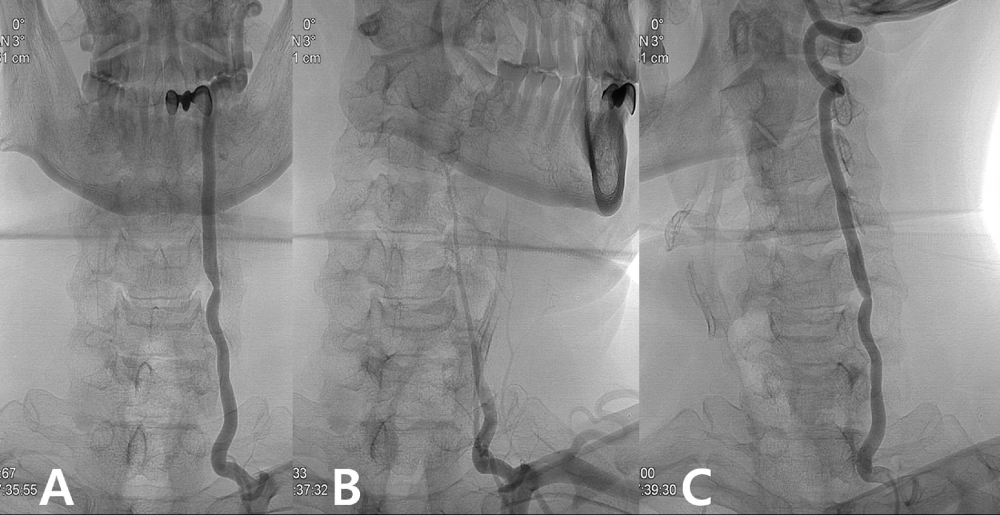

(A) Dynamic angiography shows narrowing of the left vertebral artery at the C5-6 level.

(B) The patient was positioned with his head turned 45° to the left; blood flow through the left vertebral artery was nearly completely blocked.

(C) When the patient's head was turned to the right, blood flow through the left vertebral artery was normal.

From: Lee CS, Lee HY, Yang TK. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion syndrome: misnomers and classification. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;131:18-20. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.01.016