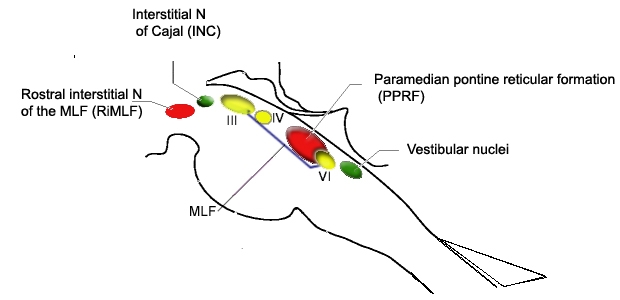

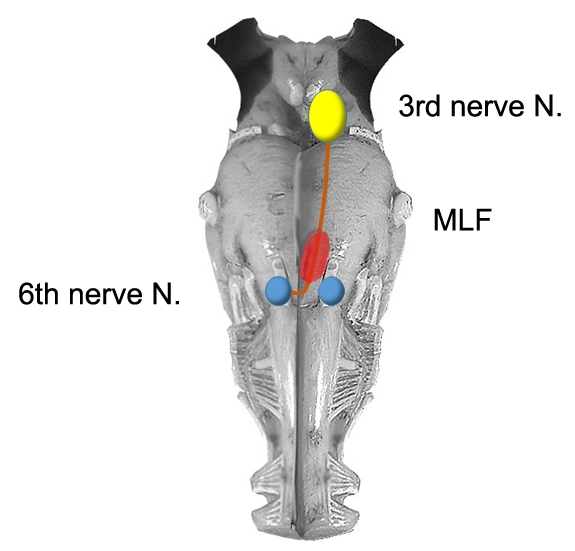

In an internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), limited adduction in one eye is due to involvement of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF), which connects the abducens and oculomotor nuclei. The interneurons of the abducens nucleus carry commands for conjugate horizonal eye movements (saccades, pursuit and the VOR) 1.

The interneurons cross at the level of the abducens nucleus, and then extend medially to the MLF, and pass up to the level of the midbrain, where they innervate the motoneurons of the medial rectus.

The lesion affects the MLF interneurons from the sixth nerve nucleus after they have crossed and are ascending. Consquently, the MLF lesion results in impaired adduction ipsilateral to the side of the lesion; the side of the failure to adduct indicates the side of the lesion.

The MLF contains fibers important for both horizontal and vertical eye movements, and carries fibres from both the anterior and posterior semicircular canals 2,3:

For horizontal gaze:

-The MLF contains axons from abducens internuclear neurons, which carry signals for horizontal saccades, VOR, and smooth pursuit

-Projects to medial rectus motoneurons in the contralateral oculomotor nucleus

For vertical gaze:

-The MLF contains axons from the riMLF, which carries vertical saccadic signals.

-Contains axons from the vestibular nuclei, which carry signals for vertical VOR, smooth pursuit, gaze holding, and otolith–ocular reflex

On eccentric gaze there is often a jerk nystagmus beating outwardly, predominantly in the abducting eye. This is an example of dissociated nystagmus, which is only present in the abducting eye.

The mechanism of abducting nystagmus in INO is unknown, although several hypotheses have been proposed. One suggests that convergence is used to help adduct the weak eye, leading to abducting nystagmus in the other eye. Alternatively, an adaptive increase in saccadic innervation might help adduct the weak eye but, because of Hering’s law of equal innervation, would also lead to abducting overshoot and nystagmus in the other eye.

Adduction and Convergence

- In a partial/mild INO, adduction will be slowed but it will be completely absent in a complete lesion. Examination of the saccades is therefore the most sensitive clinical test. Focusing on the bridge of the nose during a large horizontal saccade can help to identify subtle adduction lag in such cases4. The slow adducting saccades can be easily detected by having the patient follow an optokinetic drum or tape. Rapid phases made by the eye on the lesion side are smaller and slower5.

- Convergence should be examined and intact convergence may indicate a more caudal lesion, whereas absent convergence is seen in a higher rostral lesion, as the medial rectus subdivision of the contralateral oculomotor nucleus will also be affected; although this distinction is generally held to be unreliable3. The presence of convergence is more useful in that it can distinguish INO from a pseudo-INO, as in myasthenia gravis. In MG, convergence would be affected since all movements are affected.

- In spite of the adduction weakness most patients have normal ocular alignment, presumably due to sparing of convergence2.

- Bilateral INOs may occur in the midbrain and affect the convergence nucleus, resulting in a large-angle exotropia (meaning the eyes are deviated outward) and convergence insufficiency (the so-called wall-eyed bilateral INO (WEBINO)6.

Ocular Tilt Reaction

- Utricular signals are also carried through the MLF, and consequently an INO is often accompanied by skew deviation and other elements of the OTR. In addition to an exotropia from the INO, a hypertropia of the ipsilesional eye due to skew deviation is commonly seen acutely and is usually concomitant, ie, the hypertropia is the same in all directions of gaze (straight ahead, right, left, up, down)3.

Pursuit and VOR

- Bilateral INO may also result in impaired vertical pursuit and vestibular (VOR) eye movements, and impaired vertical gaze holding with gaze evoked nystagmus on looking up and down7(not to be confused with downbeat or upbeat nystagmus4)..

- Patients with bilateral MLF injuries commonly complain of oscillopsia with head movements due to bilateral vertical VOR impairment. Objectively, this can be demonstrated by a significant decrement in dynamic visual acuity vertically but not horizontally, or with vertical head impulse testing (HIT) in the planes of anterior and posterior SCCs8.

- During horizontal VOR testing using the head impulse test, the velocity of the adducting eye (ipsilateral to an MLF lesion) movement can be relatively preserved and is better than what would be expected based on bedside testing which shows the typical adduction lag due to an INO. This is proposed to be caused by an extra-MLF pathway, the ascending tract of Dieters, which goes directly from the vestibular nuclei to the oculomotor nucleus8.

- Spontaneous nystagmus with a torsional component may be seen with an acute MLF lesion, and is typically always ipsilesional. This may increase with removal of visual fixation, which is paradoxically usuallly a feature of peripheral vestibular disease3.

Etiology

The most common causes of INO are demyelination and infarction.

Bilateral INO is strongly suggestive of a demyelinating process7.

Myasthenia gravis can produce a pseudo-INO (this usually lacks the vertical gaze–evoked nystagmus of a true INO and is often accompanied by myasthenic eyelid signs).

(vv)Dublinino.mp4(tt)

This video includes three patients each with multiple sclerosis, and with unilateral or bilateral INOs. In the first two patients, the INOs are relatively subtle with normal adduction.

However, with rapid horizontal saccades, an adduction lag is apparent which is suggestive of an INO. The third patient also demonstrated upbeat nystagmus. Since some of the fibers responsible for vertical gaze holding travel through the MLF, upbeat nystagmus in upgaze is common with bilateral MLF lesions.

(vv)INOMS.mp4(tt)

From: Gold D. INO in multiple sclerosis. Video. [Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL Web Site]. 2016. Available at: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6tj1wb3

The video is of a patient who presented with a left INO. Adduction of the left eye was about 60% of normal and adduction of the left eye improved with convergence. On right gaze, dissociated abducting nystagmus was present in the right eye, and there was a clear adduction lag when asking her to look from left to right. With alternate cover and cover-uncover testing, there was an anticipated exodeviation of the left eye, maximal in right gaze due to the adduction deficit of the left eye.

(vv)3INO.mp4(tt)

There is also:

- Ocular tilt reaction: mild rightward head tilt, with a left hypertropia that was comitant in all directions of gaze, consistent with a skew deviation. Dilated fundoscopic examination demonstrated ocular counterroll to the right.

- Spontaneous torsional or vertical-torsional nystagmus - this patient had spontaneous (primarily) torsional nystagmus, with quick phases of the superior poles directed towards the ipsilesional (left) side. This is due to injury to the central anterior and posterior semicircular canal pathways that originated in the right labyrinth but decussated and ascended via the contralateral (left) MLF. This creates an unopposed torsional slow phase towards the right ear (generated by the unaffected left anterior and posterior canals which decussate and ascend the right MLF), with subsequent ipsiversive torsional quick phase (towards the left ear with left MLF injury).

From: Brune A, Gold D. Ocular motor & vestibular features of the MLF syndrome. Video. [Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL Web Site]. 2017. Available at: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s68m15w9