Acute unilateral vestibulopathy or vestibular neuritis (also known as vestibular neuropathy (VN)) likely arises from reactivation of a latent infection of the vestibular ganglion with herpes simplex virus type 11. There is typically no tinnitus or hearing loss, and it largely affects patients between the ages of 30 and 60 years, average about 40 years.

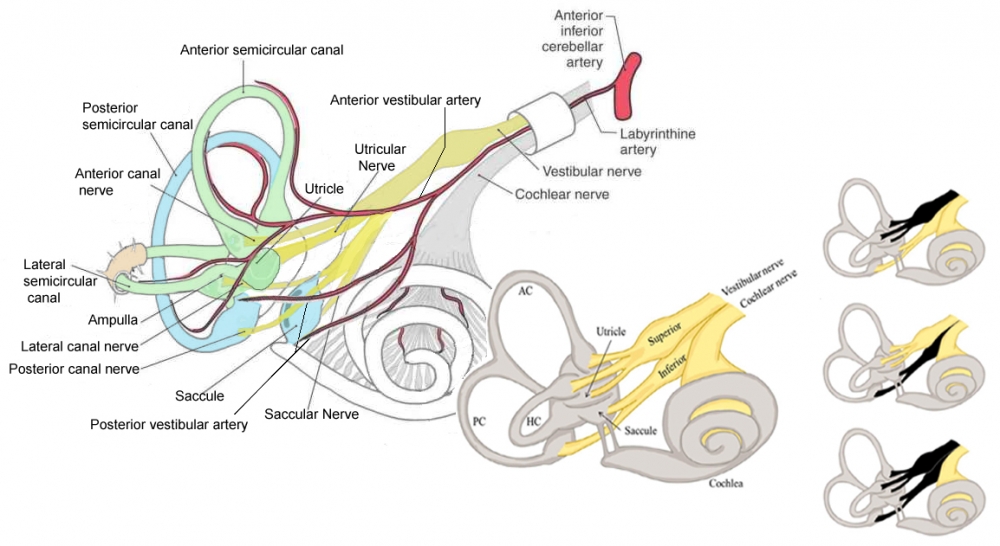

Abnormal hearing in the context of an acute vestibular syndrome could imply an infarction in the distribution of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA). The internal auditory artery, which supplies the labryrinth, is a branch of AICA.

Current criteria:

- Acute or subacute onset of sustained spinning vertigo moderate to intensity, with symptoms lasting at least 24-hours

- Presence of nystagmus fulfilling the criteria for peripheral vestibular origin: horizontal-torsional spontaneous nystagmus, enhanced by removal of visual fixation, observable for at least 24-hours after symptom onset.

- Pathological head impulse test to the suspected lesion side, i.e., coinciding with the slow phase of nystagmus. If unclear: a video HIT , indicating reduced VOR function on the side away from the spontaneous nystagmus.

- No other acute symptoms or signs indicating involvement of the central nervous system.

- Absence of central oculomotor signs indicating a central nervous system lesion. In particular, no skew deviation and no gaze evoked nystagmus in the opposite direction of the fast phase of the spontaneous nystagmus.

- No coinciding acute onset of hearing loss alternatives

Clinical Features:

Prodromal dizziness lasting a few minutes, in the few days just before the full onset of symptoms, may precede the prolonged spontaneous vertigo in as many as 25% of patients2.

The condition is a monophasic illness, and classically, VN can be said to follow a rule of 3:

- Sudden onset lasting for 3 days,

- Followed by 3 weeks of moderate symptoms,

- Then 3 months of mild symptoms3.

There is an acute or subacute onset of severe rotatory vertigo which untreated lasts for at least 24 hours. There is associated nausea/vomiting, and oscillopsia, with a sensation of spinning of the surroundings (directed away from the side of the lesion, in the direction of the quick phase of nystagmus).

The condition is, in most cases, a partial rather than a total unilateral vestibular lesion2.

According to the divisions involved, VN may be classified into distinctive types:

- Superior (common)

- Inferior (rare)

- Total (which will resemble a labyrinthitis).

The superior branch of the vestibular nerve supplies the lateral/horizontal and anterior semicircular canals, and the utricle.

The inferior branch of the vestibular nerve consists of the posterior semicircular canal and saccule.

The right hand side of the figure shows the three distinctive types, the superior, inferior, and total:

Redrawn from: Neupsy Key. The vestibular system. Retrieved from: https://neupsykey.com/the-vestibular-system-4/

Signs

- In the typical case there is a horizontal-torsional spontaneous nystagmus with the slow phases towards the affected ear. The nystagmus follows Alexander’s law, and is partially or totally suppressed with visual fixation. The nystagmus may have a vertical component that is usually upbeat reflecting the loss of anterior canal function on one side.

- The nystagmus enhances dramatically with the Dix-Hallpike test (although this test is not indicated in the acute vestibular syndrome)4.

- Pursuit away from the affected side may appear saccadic due to the nystagmus. There is no gaze-evoked nystagmus with gaze towards the affected ear.

- In the case of the rare inferior VN, the direction of the spontaneous nystagmus corresponds to the plane of the posterior canal: torsional nystagmus beating toward the unaffected side, with a downward component (the direction opposite to classical posterior canal BPPV). Since this nystagmus pattern is atypical, it may be misdiagnosed as central nystagmus2.

- The head impulse test shows impaired function of the vestibulo-ocular reflex towards the affected ear.

- Gait deviates to the affected side.

- Romberg test: there is a tendency to fall to the affected side (towards the side of the lesion). (Compensatory vestibulospinal reaction to the apparent tilt).

- The patient will rotate towards the side of the lesion when carrying out the Fukuda or Unterberger test.

- Rarely, there is an ipsiversive ocular tilt reaction (head tilt, skew deviation, and ocular torsion) and ipsiversive tilt of the subjective visual vertical (SVV). The full picture of the ocular tilt reaction, however, is not very often seen clinically, and the skew deviation is usually smaller and transient compared to central lesions

There was no loss of hearing, video head impulse test was abnormal to the right (low gain and corrective saccades), and test of skew was normal (i.e., vertical alignment was normal with alternate cover test). Per the HINTS exam (Head Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew) and in the absence of hearing loss, he was diagnosed with right-sided vestibular neuritis.

(vv)AVN.mp4(tt)

From: Gold D.Acute Vestibular Neuritis With Unidirectional Nystagmus and Abnormal Video Head Impulse Test. Video. [Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL Web Site]. 2020. Available at: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6pg73w3

Differential Diagnosis

The symptoms may be difficult to distinguish from:

- Stroke in PICA territory

- Anterior vestibular artery.

- Isolated labyrinthine infarction remains a diagnostic challenge, although is extremely rare, and usually the cochlea is also damaged5.

- Abnormal hearing in the context of an acute vestibular syndrome could imply an AICA infarction4; in addition, isolated infarction of the labyrinth may herald an infarction in the full territory of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA)5. By definition, acute hearing and other neurological symptoms, especially central oculomotor or vestibular signs (especially skew deviation), gaze saccades, gaze evoked nystagmus towards the affected ear) are absent, which is important in differentiating vestibular neuritis from central “pseudo-vestibular neuritis” caused by infarction or a multiple sclerosis lesion.

Prognosis

Complete recovery is common, with about 15% of patients having symptoms after one year. There is a low chance of recurrence.

Note that prolonged administration of medication for the treatment of vertigo delays central compensation of the peripheral vestibular deficit, and it is advised that one should carefully consider the goals of pharmacotherapy in acute unilateral vestibulopathy before proceeding. Since symptomatic therapy decreases the vestibular tone imbalance (which drives central compensation), it likely has a negative impact on central compensation and the long-term outcome. The use of vestibular exercises may be beneficial; these increase vestibular tone imbalance by head-movements, leading to increased central compensation2.

The presence of recovery may be inferred by reduction of spontaneous nystagmus, which takes about three weeks to abate, although the dynamic responses of the VOR, as shown by the positive HIT, remain impaired. Central compensation to abolish spontaneous nystagmus depends on restoration of balance between the level of spontaneous activity in the vestibular nuclei on either side.

Complications

15% of patients with VN develop “postinfectious BPPV” in the affected ear within a few weeks or months because the labyrinth is also involved1. This virtually always affects the posterior canal, and is possibly due to loosening of the otoconia of the utricle due to labyrinthine inflammation.

In patients with incomplete recovery, oscillopsia may be experienced during rapid head motion. The persistent imbalance that some patients have after acute VN may be due to many factors including inadequate central compensation, incomplete peripheral recovery, and psychophysiological and psychological features, persistent postural perceptual dizziness.