Ocular motor apraxia is an extreme instance of saccadic dysfunction, either congenital or acquired.

Other terms are Cogan syndrome or infantile saccade initiation delay syndrome (ISID), characterized by the inability to initiate saccades on command. The term ‘ocular motor apraxia’ should ideally not be used, because both saccades on command and reflexive saccades (quick optokinetic and VOR phases) may be impaired. In apraxia, reflexive saccades should be intact1.Although definitions vary, one standard definition of apraxia is an inability to voluntarily initiate a movement that can be initiated by another means, (whichreveals that a paralysis is not present).

Saccadic velocity is normal.

The saccadic impairment is not isolated, as smooth pursuit is impaired in about a third of cases. This, in combination with the developmental delay, hypotonia and speech disturbances in these children, indicates a complex impairment of the central nervous system.

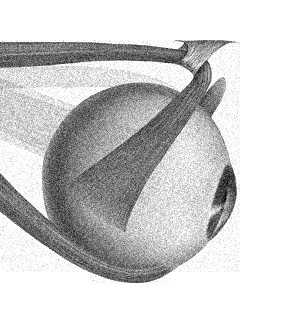

Pathophysiology

Acquired

This is usually due to bilateral hemispheric infarcts and the defect of voluntary eye movements probably reflects disruption of descending pathways both from the frontal eye fields and the parietal cortex, so the superior colliculus and brain stem reticular formation are bereft of their cortical inputs. If all voluntary eye movements are affected, involvement of frontal lobes is likely.

Congenital

In congenital OMA, saccadic velocities are normal, although often hypometric, and saccades or quick phases of nystagmus of large amplitude can occasionally be generated. These findings indicate that the premotor brain stem burst neurons that generate saccadic eye movements are intact, and the lesion is proximal to the PPRF.

The head thrusts made by affected patients probably reflect one of several adaptive strategies to facilitate changes in gaze:

- Younger patients appear to use their intact VOR, which drives their eyes into an extreme contraversive position in the orbit. As the head continues to move past the target, the eyes are dragged along in space until they become aligned with the target. Then the head rotates backward and the eyes maintain fixation as they are brought back to the central position in the orbit by the VOR.

- In contrast, older patients appear to use the head movement per se to trigger the generation of a saccadic eye movement. This strategy may reflect the use of a phylogenetically old linkage between head and saccadic eye movements that occurs reflexively in afoveate animals, when they desire to redirect their center of visual attention, since they are unable to make voluntary gaze shifts without a head movement. Thus, patients are more easily able to voluntarily shift their gaze with their heads free, a pattern of behaviour similar to that of afoveate animals,

Clinical Features

Acquired

Patients have difficulties making horizontal and vertical saccades to command and following a pointer moved by the examiner. Gaze shifts are achieved more easily with combined eye-head movements, often in association with a blink.

Vestibular eye movements (both slow and quick phases) are preserved. In addition, some patients are able to initiate saccades reflexively to novel visual targets.

In particular, bilateral lesions at the parieto-occipital junction may be associated with Balint’s syndrome, which is typically accompanied by simultanagnosia, inaccurate pointing (optic ataxia), and difficulty initiating voluntary saccades (ocular motor apraxia).

Voluntary saccades may be made more easily than in response to visual stimuli. Thus, the main abnormality appears to be a defect in the visual guidance of saccades, manifested by increased latency and decreased accuracy and impaired ability to conduct visual search. Smooth pursuit is also impaired.

Congenital

Between the ages of 4 and 6 months, characteristic, thrusting horizontal head movements develop, sometimes with prominent blinking or even rubbing of the eyelids when the child attempts to change fixation. In infants with poor head control, development of head thrusting may be delayed, and the infant may be thought to be blind since they cannot initiate saccades nor use head thrusts.

Patients show both impaired initiation or failure of initiation (increased latency) and decreased amplitude (hypometria) of voluntary saccades in response to either a simple verbal command to look left or right.

Almost all patients also show a defect in the generation of quick phases of nystagmus, which can usually be seen at the bedside by manual spinning of the patient, either when holding the child out at arm's length or by rotating the child on a swivel chair—if necessary, sitting in an adult's lap. the eyes intermittently deviate tonically in the direction of the slow phase because of a defect in the initiation of the quick phase of nystagmus.

Similarly, horizontal OKN drum rotation induces lateral gaze in the direction of drum rotation, as slow-phase pursuit movements are relatively intact. However, the failure to generate saccades consistently results in the eyes getting “locked up” in lateral gaze.

Despite difficulties in shifting horizontal gaze, vertical voluntary eye movements are normal. In congenital OMA, saccadic velocities are normal and saccades or quick phases of nystagmus of large amplitude can occasionally be generated. However, especially in younger patients, the timing and amplitude (but not velocity) of quick phases of vestibular and optokinetic nystagmus may be impaired.

Sometimes the saccade defect (and head thrusts) is asymmetric.

Pursuit eye movements may also be of low gain, but the corrective saccades are usually promptly generated.

Blinks may speed up abnormally slow saccades in patients with degenerative or other diseases. In this case, the blink may cause a more synchronized and complete inhibition of the omnipause neurons, thus allowing the burst neurons a better chance to discharge. This may also be the mechanism that patients with ocular motor apraxia employ (along with a head movement) to initiate a saccade.

Affected patients usually improve with age: The head movements become less prominent as the patients are better able to direct their eyes voluntarily.

Causes

Congenital ocular motor apraxia is idiopathic.

Acquired ocular motor apraxia is caused by bilateral fronto-parietal lesions, often as a result of an anoxic event, or it may be a complication of cardiopulmonary bypass.

Huntington's disease: patients show a greater increase in latency for initiating saccades on command than for more reflexive saccades to novel visual stimuli

Other causes of horizontal saccade failure, which may affect both horizontal and vertical saccades:

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease

Niemann-Pick disease type C

Gaucher disease

Tay-Sachs disease

Abetalipoproteinemia

Wilson disease

GM1 gangliosidosis

Krabbe's leukodystrophy

Peroxisomal disorders

Lesch-Nyhan disease

Proprionic academia

Cornelia de Lange syndrome

Ataxia telangiectasia

Developmental abnormalities of the midline cerebellum (Joubert syndrome)

Purely vertical ocular motor apraxia is rare and usually reflects direct involvement of saccade-generating pathways in the midbrain or pons

This boy shows all the characteristic ocular motor signs of congenital ocular motor apraxia (OMA): intermittent failure to initiate horizontal saccades to right and left; rapid head thrusts to fixate a target.

When the eyes are looking to the right, in order to fixate a target in primary position, the child thrusts his head to the left to trigger vestibular induced saccades to change gaze. The head overshoots the position of the target of attention but, once fixation is attained, the head turns back to the primary position. The sequence of events is completed in a matter of seconds.

Tonic lateral deviation of the eyes present on sustained (vestibular) rotation of the body were noted (but are not illustrated on the video).

(vv)COMA1.mp4(tt)

From: Wray S. Congenital Ocular Motor Apraxia. Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library. Retrieved from: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6jd7tbp

This infant shows all the characteristic ocular motor signs of congenital ocular motor apraxia (OMA).

(vv)COMA2.mp4(tt)

From: Wray S. Congenital Ocular Motor Apraxia. Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library. Retrieved from: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6dr5s07

(vv)FTD.mp4(tt)

From: Wray S. Ocular Motor Apraxia. Neuro-Ophthalmology Virtual Education Library. Retrieved from: https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s61g3htr