Functional and psychiatric disorders that cause vestibular symptoms (vertigo, unsteadiness, and dizziness) are common, more so than many well known structural vestibular disorders1. Functional refers to conditions that arise from changes in the functioning of organ systems, rather than from structural defects or psychiatric disorders, which are separate entities. Functional vertigo and dizziness represent new nomenclature for disorders known in the past as somatoform or psychosomatic dizziness.

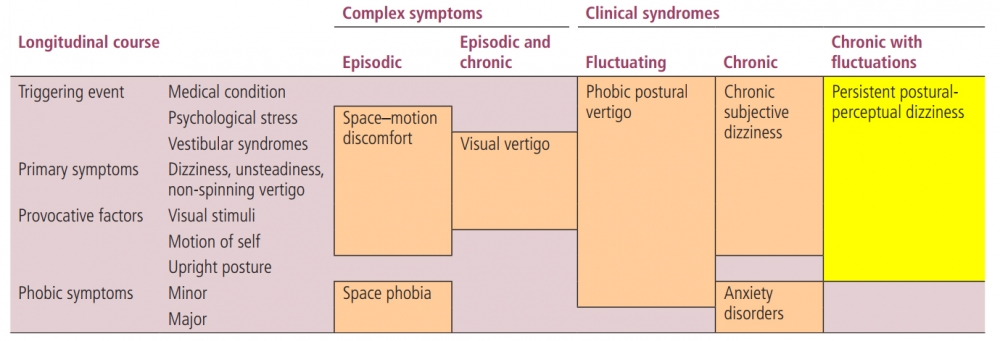

There is now published consensus on the criteria of the disorder termed ‘persistent postural-perceptual dizziness’ (PPPD)2. PPPD includes core features described over the last 30 years in syndromes like phobic postural vertigo (PPV), chronic subjective dizziness (CSD), space-motion discomfort (SMD) , and visual vertigo. Features common to these syndromes formed the basic diagnostic criteria of PPPD.

PPV was the term which was used prior to use of the term PPPD; patient symptoms were the expression of an enhanced degree of visual dependence in patients with an undetected vestibular problem and the term “visual vertigo” was introduced3. Other terms that have been used include “space motion discomfort” and “visual vestibular mismatch”. A further term “visually induced dizziness” was also introduced, which emphasized the concept of visual dependence4.

Several studies have shown a number of functional alterations of vestibular and balance mechanisms which distinguished PPV and CSD from primary psychiatric disorders, and are applicable to the new entity PPPD. PPV, CSD, SMD, and visual vertigo share a number of features, and their differences may reflect various perspectives on a single multifaceted clinical entity or offer insights into potentially distinguishable subtypes of PPPD such as postural sensitivity or visual sensitivity1.

From: Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018 Feb;18(1):5-13. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001809. Epub 2017 Dec 5. PMID: 29208729.

The criteria for the diagnosis of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness2

A. One or more symptoms of dizziness, unsteadiness, or non-spinning vertigo are present on most days for 3 months and more:

1. Symptoms are persistent, but wax and wane

2. Symptoms tend to increase as the day progresses but may not be active throughout the entire day

3. Momentary flares may occur spontaneously or with sudden movements

B. Symptoms are present without specific provocation but are exacerbated by

1. Upright posture

2. Active or passive motion without regard to direction or position

3. Exposure to moving visual stimuli or complex visual patterns

C. The disorder usually begins shortly after an event that causes acute vestibular symptoms or problems with balance, though less commonly, it develops slowly

1. Precipitating events include acute, episodic, or chronic vestibular syndromes, other neurologic or medical illnesses, and psychological distress

a. When triggered by an acute or episodic precipitant, symptoms typically settle into the pattern of criterion A as the precipitant resolves, but may occur intermittently at first, and then consolidate into a persistent course

b. When triggered by a chronic precipitant, symptoms may develop slowly and worsen gradually

D. Symptoms cause significant distress or functional impairment

From: Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018 Feb;18(1):5-13. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001809. Epub 2017 Dec 5. PMID: 29208729.

Symptoms

Unsteadiness and non-spinning vertigo tend to dominate the clinical picture.

Symptoms are exacerbated by5:

- Uright posture

- Moving about actively or being moved passively (eg, standing, walking or riding in a vehicle)

- Being immersed in environments with complex or moving visual stimuli (eg, a hallway with complex patterned carpet, a supermarket aisle, looking at traffic). Visual hypersensitivity, which can occur in isolation as the symptom of ‘visual vertigo’3,is a characteristic feature of PPPD.

Dizziness, unsteadiness and vertigo are difficult to describe and symptoms might include5:

- Non-spinning motion

- Swaying as if on a boat

- Unsteadiness, with associated fear of falling

- Lightheadedness, as if about to pass out.

In PPPD, usually the worsening of symptoms builds up with repeated movements and when the patient is at rest, the symptom complex takes time (hours or more) to return to the usual baseline. This is different from the dizziness of uncomplicated unilateral vestibular loss, which is time-locked to the movement and stops straight away at rest6.

Visual Dependence

In some respects, PPPD has more evident disorders of physiological function than other neurological conditions, as illustrated by visual dependence. PPPD causes chronic dizziness and unsteadiness, which worsen when exposed to visual motion, self motion, or when performing precision visual tasks like reading6. Visual dependence is a condition which induces symptoms arising from static or moving visual cues in the environment, and may be isolated or combined with intolerance of passive/active body movements. Visual dependence can also result in signs, such as impaired balance, which are often described by patients as an “inherent sense of instability”, and which may be measured7.

It is unclear how visual dependence develops, but it may be defined as the reduced ability to disregard visual cues in complex, large field, or conflicting visual environments. Visual dependence is also associated with other conditions, including vestibular diseases, anxiety, motion sickness, and migraine. If visually induced vertigo is combined with high levels of anxiety, it can lead to agoraphobia as large spaces may be disorienting for visually dependent patients 8. Symptoms and signsof visual dependence can be provoked by an overabundance of visual cues in certain visual environments that were previously coped with, including crowds, traffic, supermarkets, etc. Age-related development of visual dependence may be the result of a reduction in the capacity to use visual inputs correctly. Vestibular hypersensitivity may also be related to an inability to suppress stimuli that are environmentally inaccurate (eg, moving train, 3D movies).

Precipitants

The majority of conditions that precede PPPD are acute or episodic in nature. Patients report the onset of chronic symptoms of PPPD following their acute illnesses. Triggering factors for visual dependence include2:

1. Vestibular end organ diseases, eg, vestibular neuritis, which provoke an increase in the visual contribution within the framework of the sensory integration process, often leading to difficulties in resolving various spatial daily situations where the whole body is implicated. Visual dependence frequently occurs in patients with a history of past vestibular disease and visual dependence can be generated by the compensation process occurring after the vestibular insult.

2. Vestibular migraine or conflicting visual inputs.

3. Psychiatric situations (ie, environmental situations including panic and anxiety, which may be generated by stimuli such as watching the movement of water).

4. Brain trauma (including blunt force trauma).

Patients may give accounts of avoiding provocative situations with resultant impairment in social and occupational activities. Patients with PPPD may be quite consumed by their problem and present at their ‘wits end’. They may describe anticipatory anxiety or incapacitation in situations where dizziness would be particularly problematic such as stairs or roads. When these secondary phobic thoughts and avoidance behaviours reach a distressing or disabling level, they warrant the additional diagnosis of a specific phobia such as fear of dizziness, fear of falling or agoraphobia5

Gait Disorder

Gait may be slow or hesitant gait and/or a ‘walking on ice’ gait pattern.. Distraction techniques during standing and walking can provide positive evidence that the unsteadiness has a broadly functional basis.During standing, this can be achieved by asking the patient to name a number written on their back or with a motor task such as using a phone or testing eye movements. These are usually more effective than mental distraction such as serial sevens or listing months backwards.

Counterintuitively, more demanding postural tasks, such as standing in tandem position or walking backwards, can also normalise body sway and gait5.

Diagnosis

Patients’ account of symptom intensity, persistence and impairment in daily activities might appear at odds with their relatively benign appearance on casual observation in the clinic. However, as in many functional neurological disorders, clinical ‘inconsistencies’ (eg, reports of persistent symptoms, but retained abilities to manage complex tasks intermittently when necessary) are a typical feature of attention-modulated disorders, and not signs of inauthenticity or malingering.

Information Sheet Information Sheet for patients with PPPD

From: https://www.neurosymptoms.org/dizziness/4594358005